In early December of 2012, I was asked to participate in a program to sterilize dogs on the Bahamian island of New Providence. The program, organized by the non-profit Animal Balance, was a joint endeavor between Bahamian veterinary and animal welfare organizations, Animal Balance, and a wide array of veterinary professionals, animal catchers, and volunteers from seven countries whose combined goal it was to sterilize an incredible 2,000 or more dogs in a mere two weeks.

The issue of loose dogs on New Providence has been a concern for citizens, government, visitors, and animal welfare supporters for many years. Many communities around the world face the difficulty of managing large populations of free-roaming dogs, and the island of New Providence has a population of approximately 20,000.

Operation Potcake?

Traditionally, potcake refers to the inch or two of compacted, charred remains of rice and peas at the bottom of Bahamian pot-baked dishes. Instead of being discarded, this rice cake was put out for the street dogs as their primary source of nutrition. In time, the islanders began to refer to the dogs themselves as potcakes, and the name has stuck. Generations of tourists coming to enjoy the pristine scenes of the Bahamas have fallen in love with potcakes and given them a reputation throughout the world as loveable street dogs.

Putting it Together

Community based sterilization programs set out to achieve three basic goals: Improved quality of life for street animals, improved quality of life for residents, and decrease the number of animals on the streets. The recent clinics on New Providence did all that and more. In all, five clinics were set up across the 20-mile long island. Residents were encouraged to bring their dogs to the clinics for sterilization and basic treatment. Teams of veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and volunteers at each site documented the animals, processed them for surgery, nursed them through recovery, and made them comfortable until they were reunited with their owners or returned to their territory. Meanwhile, the team I was a part of was tasked to go out and catch dogs that otherwise would not make it to the clinics either because of distance, lack of transport, or because the dogs were not owned.

My Perspective

In Kuwait, I manage a program that has been catching dogs at a rate of 1,500 per year for nearly two years now. Many of our dogs are exceedingly difficult to catch because they have faced so much intentional cruelty like being shot at, having things thrown at them, and being chased by vehicles. They are, as a result, very difficult to catch, and it requires a unique skillset to do so. I was therefore very interested to see how my experience, which has been limited to Kuwait and a few Asian countries, would hold up on an island in the south Atlantic.

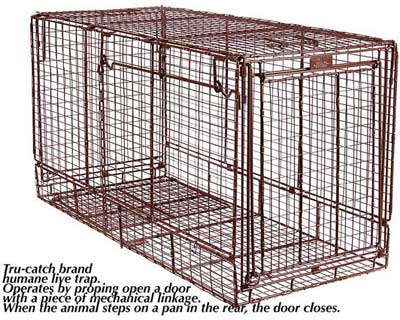

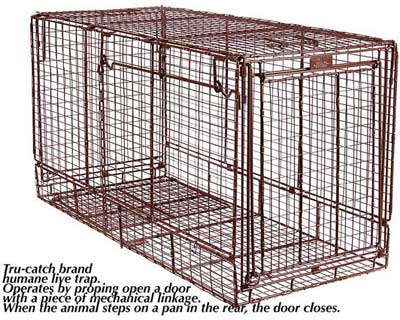

Once on the island, I was assigned to a team of four including an animal control technician, a veterinary technician, a local volunteer, and myself. We were given a number of humane live traps (photo above) and a quota for the number of animals we needed to bring back to the clinic every day. Our destinations were low-income neighborhoods where loose dogs were prevalent. We could guess what kind of dogs we would encounter, but we had no idea what kind of people we might meet. It turned out that most of the people we met were absolutely wonderful. On arrival in each area, residents would expostulate: “What are you doing with that dog!” With an explanation that we were taking the dogs to be sterilized and treated then returned within two days, their wall of concern would immediately break down and they would engage all of their friends, neighbors, and family members to bring us their dogs. It was incredible to see. When we found a dog that didn’t seem like it lived in front of a particular house, we would just ask. Someone always knew if the dog was “owned” (some dogs were kept in yards or chained while others were ‘owned’ but loose) or not. People knew every dog on their street. If the owner was inside or away from home, someone would go and get them or make a phone call and set up a time for us to collect the animal. News of our presence would spread like wildfire on every street, and it seemed like every man, woman, and child was ready to help in some way. I was especially amazed and pleased when I caught a dog named Pablo whose brindle coat and friendly personality made him an instant favorite. After placing him on a truck and driving to a different neighborhood to collect more dogs, two kids came up to us on bikes and said “Hey! I know that dog! That’s Pablo!” It was very uplifting to see the communities so engaged in improving the lives of their dogs.

After the first day in the field, we realized that much of our work was not going to be the complex system of trapping difficult dogs I had become so used to in Kuwait. Rather, we found we could simply enter these little micro-communities of a few houses on a side road and tell them what we were doing and how it would help them. We therefore didn’t have to do very much difficult capture. Most of our work became opening cage doors, doing paper work, and carrying the ‘trapped’ dogs around the trucks and clinics. Still, there were plenty of dangerous dogs that required more skill to catch and handle. There were also some truly feral dogs to catch, and I was happy to see that the methods we use in Kuwait are pretty much the same as those people are using around the world.

Bringing it Home

In the end, Operation Potcake sterilized 2,315 dogs in 10 days—a truly phenomenal number. But the true success of this project was not in numbers, no matter how impressive. Operation Potcake proved that when a few passionate people put their hearts, and just as importantly their heads, together toward a common goal, they can bring together communities, change the thinking of a government, inspire a people, and give new value to even so humble a creature as a Bahamian Potcake. Operation Potcake is now a five-year program that will build upon itself and work toward the goal of sterilizing most of the 20,000 dogs on New Providence, and because of the success of the initial operation, the government has now bought into the program. They are now adopting sterilization as a primary method of population control throughout all of the Bahamian islands.

Kuwait has an even bigger problem. We have close to 10,000 feral dogs roaming areas outside of the city, and no one can even estimate the number of cats on the streets. There are certainly hundreds of thousands of the latter. K’S PATH, with our limited funding and staff, is only currently able to handle a few thousand animals each year. However, we have worked tirelessly over the past five years to gain an expert understanding of the root cause of the problem, and we have the knowledge to implement solutions. Industry, namely Kuwait Oil Company and Saudi Arabian Chevron have already taken notice and made us their exclusive contractor for animal population management. For us, our “Operation Potcake” has been completed many times over. We retain the proof of our accomplishments, and we’ve submitted them to the government of Kuwait. We stand ready to act, but we simply cannot do this alone.

Post by John Peaveler

Managing Director

Kuwait Society for the Protection of Animals and Their Habitat (K’S PATH)